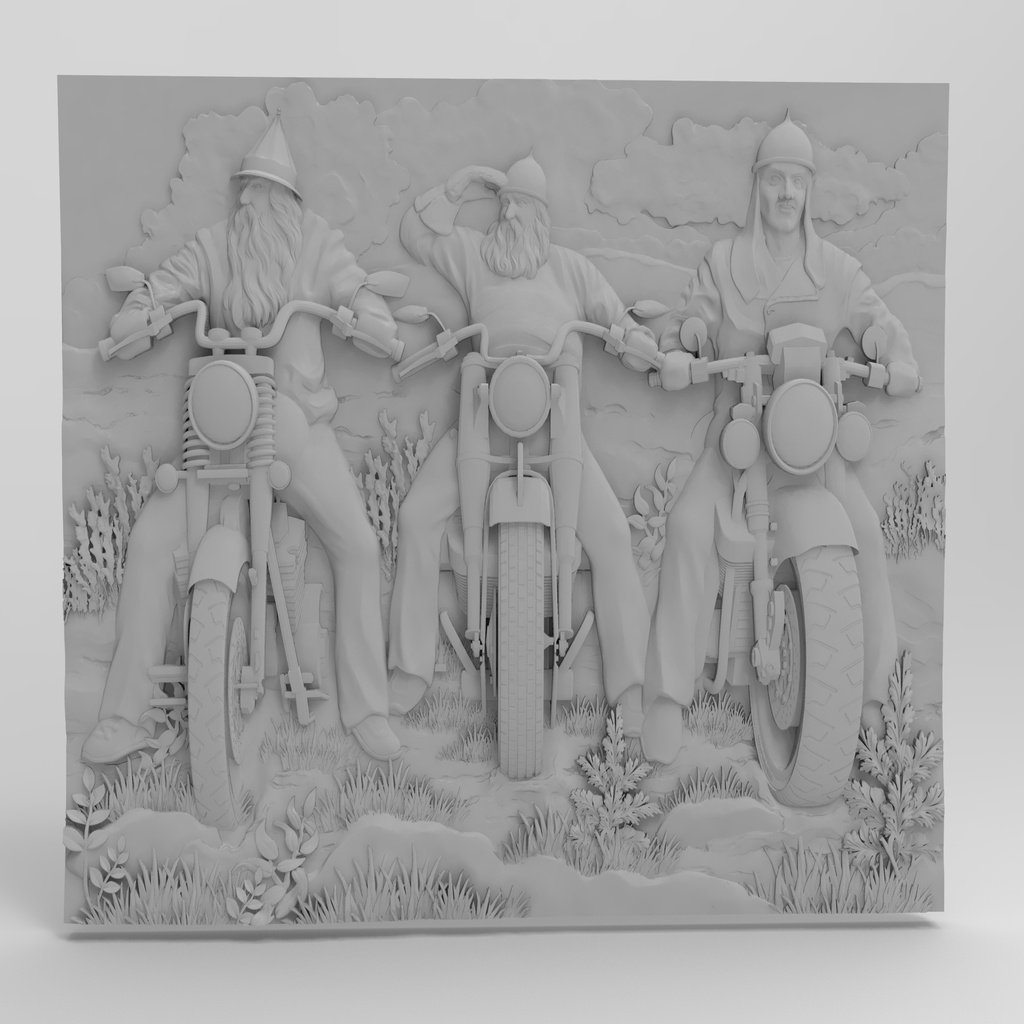

3 Bogatyr bikers For CNC

thingiverse

Bogatyr From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to navigationJump to search This article is about the medieval epic heroes. For other uses, see Bogatyr (disambiguation). Three of the most famous bogatyrs, Dobrynya Nikitich, Ilya Muromets and Alyosha Popovich, appear together in Victor Vasnetsov's 1898 painting Bogatyrs. A bogatyr (Russian: богатырь, IPA: [bəɡɐˈtɨrʲ] (About this soundlisten)) or vityaz (Russian: витязь, IPA: [ˈvʲitʲɪsʲ]) is a stock character in medieval East Slavic legends, akin to a Western European knight-errant. Bogatyrs appear mainly in Rus' epic poems - bylinas. Historically, they came into existence during the reign of Vladimir the Great (Grand Prince of Kiev from 980 to 1015) as part of his elite warriors (druzhina[1]), akin to Knights of the Round Table.[2] Tradition describes bogatyrs as warriors of immense strength, courage and bravery, rarely using magic while fighting enemies[2] in order to maintain the "loosely based on historical fact" aspect of bylinas. They are characterized as having resounding voices, with patriotic and religious pursuits, defending Rus' from foreign enemies (especially nomadic Turkic steppe-peoples or Finno-Ugric tribes in the period prior to the Mongol invasions) and their religion.[3] In modern Russian, the word bogatyr labels a courageous hero, an athlete or a physically strong person.[4] Contents 1 Etymology 2 Overview 3 Female Bogatyr 4 Famous bogatyrs 5 Bogatyrs in films 6 Bogatyrs in books 7 See also 8 References 8.1 Citations 8.2 Sources Etymology Photo of bogatyr definition from Oxford Russian-English Dictionary, depicting the derivations The word bogatyr is not originally Russian. There have been different theories[5] about the origin of the word but researchers agree that bogatyr is not of Slavic origin.[6] Many researchers suspect[6] the word bogatyr is derived from a Turco-Mongolian word: baatar, bagadur, baghtur, bator, batyr, and batur, all with meanings along the lines of hero, warrior, and brave. This reasoning originates from noted interactions between Turco-Mongols and Rus-Kievan people in the form war and battle, the chance of one influencing the other and vice versa being high. The word bogatyr is used similarly in other modern languages such as Polish (bohater), Hungarian (bátor) and Persian (bahadur), meaning hero, brave and/or athlete. The first time bogatyr is used to denote "hero" and subsequently becoming synonymous with each other was recorded in Stanisław Sarnicki's book Descriptio veteris et novae Poloniae cum divisione ejusdem veteri et nova (A description of the Old and the New Poland with the old, and a new division of the same), printed in 1585 in Cracow (in the Aleksy Rodecki's printing house), in which he says, "Rossi… de heroibus suis, quos Bohatiros id est semideos vocant, aliis persuadere conantur."[5] ("Russians... try to convince others about their heroes whom they call Bogatirs, meaning demigods.") Overview Knight at the Crossroads, Viktor Vasnetsov (1882) Many Rus epic poems, called Bylinas, prominently featured stories about these heroes, as did several chronicles, including the 13th century Galician–Volhynian Chronicle. Some bogatyrs are presumed to be historical figures, while others, like the giant Svyatogor, are purely fictional and possibly descend from Slavic pagan mythology. The epic poems are usually divided into three collections: the Mythological epics, older stories that were told before Kiev-Rus was founded and Christianity was brought to the region, and included magic and the supernatural; the Kievan cycle, that contains the largest number of bogatyrs and their stories(IIya Muromets, Dobrynya Nikitich, and Aloysha Popovich); and the Novgorod cycle, focused on Cadko and Vasily Buslayev, that depicts everyday life in Novgorod.[7] Andrei Ryabushkin. Sadko, a rich Novgorod merchant, 1895. Many of the stories about bogatyrs revolve around the court of Vladimir I of Kiev (958–1015) and are called the Kievan Cycle. The most notable bogatyrs or vityazes served at his court: the trio of Alyosha Popovich, Dobrynya Nikitich and Ilya Muromets. Each of them tends to be known for a certain character trait: Alyosha Popovich for his wits, Dobrynya Nikitich for his courage, and Ilya Muromets for his physical and spiritual power and integrity, and for his dedication to the protection of his homeland and people. Most of those bogatyrs adventures are fictional, and often included fighting dragons, giants and other mythical creatures. However, the bogatyrs themselves were often based on real people. Historical prototypes of both Dobrynya Nikitich (the warlord Dobrynya) and Ilya Muromets are proven to have existed. The Novgorod Republic produced a specific kind of hero, an adventurer rather than a noble warrior. The most prominent examples were Sadko and Vasily Buslayev who became part of the Novgorod Cycle of folk epics.[7] Mythological epics rooted in the supernatural and shamanism, and related to paganism.[7] The most prominent heroes in these epics are Syvatogor and Volkh Vseslavyevich; they are commonly called the "Elder Bogatyrs". Later notable bogatyrs also include those who fought by Alexander Nevsky's side, including Vasily Buslayev and those who fought in the Battle of Kulikovo. Bogatyrs and their heroic tales have influenced many figures in Russian Literature and Art, such Alexander Pushkin, who wrote the 1820 epic fairy tale poem Ruslan and Ludmila, Victor Vasnetsov, and Andrei Ryabushkin whose artworks depict many bogatyrs from the different cycles of folk epics. Bogatyrs are also mentioned in wonder tales in a more playful light as in Foma Berennikov,[8] a story in Aleksandr Afanas'ev's collection of tales called Russian Fairy Tales featuring Alyosha Popovich and Ilya Muromets. Motorcycling From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to navigationJump to search "Motorcyclist" redirects here. For the US motorcycling magazine, see Motorcyclist (magazine). See also: Outline of motorcycles and motorcycling Three riders on a motorcycle in Tehran Motorcycle social activity File:20130622 04 Ne u Pišece već.webm A video of a person riding a motorcycle Motorcycling is riding a motorcycle. For some people, motorcycling may be the only affordable form of individual motorized transportation, and small-displacement motorcycles are the most common motor vehicle in the most populous countries, including India, China and Indonesia.[1][2][3][4] In developing countries, motorcycles are overwhelmingly utilitarian due to lower prices and greater fuel economy. Of all motorcycles, 58% are in the Asia Pacific and Southern and Eastern Asia regions, excluding car-centric Japan. Motorcycles are mainly a luxury good in developed nations, where they are used mostly for recreation, as a lifestyle accessory or a symbol of personal identity. Beyond being a mode of motor transportation or sport, motorcycling has become a subculture and lifestyle. Although mainly a solo activity, motorcycling can be social and motorcyclists tend to have a sense of community with each other.[5][6] Contents 1 Reasons for riding a motorcycle 1.1 Speed appeal 1.2 Benefits when commuting 2 Demographics 2.1 Propagation 2.1.1 Changes in propagation 2.2 Usage in the developed world 3 Safety 3.1 Causes for motorcycle accidents 3.2 Helmet usage 4 Subcultures 5 Clubs, lobbying groups, and outlaw gangs 5.1 Motorcycle clubs 5.2 Lobbying 5.3 Outlaw gangs 6 Maintenance 7 Notes 8 References 9 External links Reasons for riding a motorcycle A motorcyclist For most riders, a motorcycle is a cheaper and more convenient form of transportation which causes less commuter congestion within cities and has less environmental impact than automobile ownership. Others ride as a way to relieve stress and to "clear their minds" as described in Robert M. Pirsig's book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Pirsig contrasted the sense of connection experienced by motorcyclists with the isolation of drivers who are "always in a compartment", passively observing the passing landscape. Pirsig portrayed motorcycling as being in "completely in contact with it all... in the scene."[7] The connection to one's motorcycle is sensed further, as Pirsig explained, by the frequent need to maintain its mechanical operation. Pirsig felt that connection deepen when faced with a difficult mechanical problem that required walking away from it until the solution became clear. Similarly, motorcyclists experience pleasure at the feeling of being far more connected to their motor vehicles than in a motorcar, as being part of it rather than in it.[8] Speed appeal Speed draws many people to motorcycling because the power-to-weight ratio of even a low-power motorcycle is in league with that of an expensive sports car. The power-to-weight ratio of many modestly priced sport bikes is well beyond any mass-market automobile and rivals that of supercars for a fraction of the price.[9] The fastest accelerating production cars, capable of 0 to 60 mph (0 to 97 km/h) in under 3.5 seconds, or 0 to 1⁄4 mile (0.0 to 0.4 km) in under 12 seconds is a relatively select club of exotic names like Porsche and Lamborghini, with a few extreme sub-models of popular sports cars, like the Shelby Mustang, and mostly made since the 1990s. Conversely, the fastest accelerating motorcycles meeting the same criteria is a much longer list and includes many non-sportbikes, such as the Triumph Tiger Explorer or Yamaha XT1200Z Super Ténéré, and includes many motorcycles dating back to the 1970s. Hunter S. Thompson's book Hell's Angels includes an ode to the joys of pushing a motorcycle to its limits, "with the throttle screwed on there is only the barest margin, and no room at all for mistakes ... that's when the strange music starts ... fear becomes exhilaration [and the] only sounds are the wind and a dull roar floating back from the mufflers"[10] and T. E. Lawrence wrote of the "lustfulness of moving swiftly" and the "pleasure of speeding on the road". A sensation he compared to feeling "the earth moulding herself under me ... coming alive ... and heaving and tossing on each side like a sea."[11] Benefits when commuting Milk delivery in Karnal, India While people choose to ride motorcycles for various reasons, those reasons are increasingly practical, with riders opting for a powered two-wheeler as a cost-efficient alternative to infrequent and expensive public transport systems, or as a means of avoiding or reducing the effects of urban congestion.[12] Where permitted, lane splitting, which is also known as filtering, allows motorcycles to move between vehicles in slow or stationary traffic.[13] In the UK, motorcycles are exempt from the £11.50 per day London congestion charge[14] that other vehicles must pay to enter the city during the day. Motorcycles are also exempt from toll charges at such river crossings as the Dartford Crossing, and Mersey Tunnels. Such cities as Bristol provide dedicated free parking and allow motorcycles to use bus lanes. In the United States, motorcycles may use high-occupancy vehicle lanes in accordance with federal law [15] and pay a lesser fee on some toll roads and toll bridges. Other countries have similar policies. In New Zealand, motorcycle riders need not pay for parking that is controlled by a barrier arm;[16] the arm occupies less than the entire width of the lane, and the motorcyclist simply rides around it.[17] Many car parks that are thus controlled so supply special areas for motorcycles to park as to save space. In many cities that have serious parking challenges for cars, such as Melbourne, Australia, motorcycles are generally permitted to park on the sidewalk, rather than occupy a space on the street which might otherwise be used by a car. Melbourne presents an example for the rest of the world with its free motorcycle footpath parking which is enshrined in their Future Melbourne Committee Road Safety Plan[18] On Washington State Ferries, the most-used vehicle ferry system in the United States, motorcycle riders get priority boarding, skip automobile waiting lines, and are charged a lower fare than automobiles.[19][20] BC Ferries users obtain many of the same benefits.[21] Demographics A couple ride on a motorcycle in Udaipur, India Statistically, there is a large difference between the car-dominated developed nations, and the more populous developing countries where cars are less common than motorcycles. In developed nations, motorcycles are frequently owned in addition to a car, and thus used primarily for recreation or when traffic density means a motorcycle confers travel time or parking advantages as a mode of transport. In the developing world a motorcycle is more likely to be the primary mode of transport for its owner, and often the owner's family as well. It is not uncommon for riders to transport multiple passengers or large goods aboard small motorcycles and scooters simply because there is no better alternative. Cost of ownership considerations regarding maintenance and parts, especially in remote areas, often place cars beyond the reach of families who find motorcycles comparatively affordable.[22] The simplicity demanded of motorcycles used in the developing world, coupled with the high volume of sales possible makes them a profitable and appealing product for major manufacturers, who go to substantial lengths to attract and retain market share.[23] Propagation Number of motorcycles vs number of cars by country. Size of pie indicates population - 2002 estimates[24][25] Motorbikes are one of the most affordable forms of motorised transport and, for most of the world's population, they are the most familiar type of motor vehicle.[1][2][3] While North America, Europe and Japan are car-centric cultures where motorcycles are uncommon, the non-car-centric cultures of India, China and Southeast Asia account for more than half of the world's population, and in those places two-wheelers outnumber four wheeled vehicles. About 200 million motorcycles, including mopeds, motor scooters, motorised bicycles, and other powered two and three-wheelers, are in use worldwide,[26] or about 33 motorcycles per 1000 people. By comparison, there are about 1 billion cars in the world, or about 141 per 1000 people, with about one third in service in Japan and the United States.[27] Millions of cars (light blue) and motorcycles (dark blue) in the top 20 countries with the most motorcycles. Population in red. 2002 estimates.[24][25] The four largest motorcycle markets in the world are all in Asia: China, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam.[1][28] India, with an estimated 37 million motorcycles/mopeds, was home to the largest number of motorised two wheelers in the world. China came a close second with 34 million motorcycles/mopeds in 2002.[24][25] As the middle class in India, China, and other developing countries grows, they are repeating the transition from motorcycles to cars that took place in the US in the years after World War I, and in Europe following World War II, and the role of motorcycling is changing from a transport necessity to a leisure activity, and the motorcycle is changing from a family's primary motor vehicle to a second or third vehicle. The motorcycle is also popular in Brazil's frontier towns.[3] Motorbikes are the primary form of transportation in Vietnam In numerous cultures, motorcycles are the primary means of motorised transport. According to the Taiwanese government, for example, "the number of automobiles per ten thousand population is around 2,500, and the number of motorcycles is about 5,000."[29] In places such as Vietnam, motorised traffic consist of mostly motorbikes[2] due to a lack of public transport and low income levels that put automobiles out of reach for many.[1] Outlaw motorcycle club From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to navigationJump to search This article is about non-AMA sanctioned motorcycle clubs. For the club established in McCook, Illinois in 1935, see Outlaws Motorcycle Club. For general types of motorcycling groups, see Motorcycle club. "Motorcycle gang" redirects here. For the films, see Motorcycle Gang (1957 film) and Motorcycle Gang (1994 film). Motorcycle club members meet at a run in Australia in 2009. An outlaw motorcycle club, is a motorcycle subculture. It is generally centered on the use of cruiser motorcycles, particularly Harley-Davidsons and choppers, and a set of ideals that celebrate freedom, nonconformity to mainstream culture, and loyalty to the biker group. In the United States, such motorcycle clubs (MCs) are considered "outlaw" not necessarily because they engage in criminal activity, but because they are not sanctioned by the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) and do not adhere to the AMA's rules. Instead the clubs have their own set of bylaws reflecting the outlaw biker culture.[1][2][3][4][5] The U.S. Department of Justice defines "outlaw motorcycle gangs" (OMG) as "organizations whose members use their motorcycle clubs as conduits for criminal enterprises".[6] Contents 1 Organization and leadership 2 Membership 3 Biker culture 3.1 Charity events 4 Identification 4.1 One-, two-, and three-piece patches 4.2 One percenter 4.3 Other patches 5 Gender and race 6 Outlaw motorcycle clubs and crime 7 Outlaw motorcycle clubs as criminal enterprises 8 Relationships between outlaw motorcycle clubs 9 Cultural influence 9.1 In popular culture 9.1.1 Literature 9.1.2 Television 9.1.3 Video games 10 See also 11 Notes 12 References 13 Sources 14 External links Organization and leadership The Hells Angels MC New York City clubhouse, with many security cameras and floodlights on the front of the building While organizations may vary, the typical internal organization of a motorcycle club consists of a president, vice president, treasurer, secretary, road captain, and sergeant-at-arms (sometimes known as enforcer).[7] Localized groups of a single, large MC are called chapters and the first chapter established for an MC is referred to as the mother chapter. The president of the mother chapter serves as the president of the entire MC, and sets club policy on a variety of issues. Larger motorcycle clubs often acquire real estate for use as a clubhouse or private compound. Membership Some "biker" clubs employ a process whereby members must pass several stages such as "friend of the club", "hang-around", and "prospect", on their way to becoming full-patch (see explanation of 'patching' below) members.[8] The actual stages and membership process can and often does vary widely from club to club. Often, an individual must pass a vote of the membership and swear some level of allegiance to the club.[8] Some clubs have a unique club patch (cut or top rocker)[9] adorned with the term MC that are worn on the rider's vest, known as a kutte. In these clubs, some amount of hazing may occur during the early stages (i.e. hang-around, prospecting) ranging from the mandatory performance of menial labor tasks for full patch members to sophomoric pranks, and, in rare cases with some outlaw motorcycle clubs, acts of violence.[10] During this time, the prospect may wear the club name on the back of their vest, but not the full logo, though this practice may vary from club to club. To become a full member, the prospect or probate must be voted on by the rest of the full club members. Successful admission usually requires more than a simple majority, and some clubs may reject a prospect or a probate for a single dissenting vote. A formal induction follows, in which the new member affirms his loyalty to the club and its members. The final logo patch is then awarded. Full members are often referred to as "full patch members" or "patchholders" and the step of attaining full membership can be referred to as "being patched".[11]

With this file you will be able to print 3 Bogatyr bikers For CNC with your 3D printer. Click on the button and save the file on your computer to work, edit or customize your design. You can also find more 3D designs for printers on 3 Bogatyr bikers For CNC.