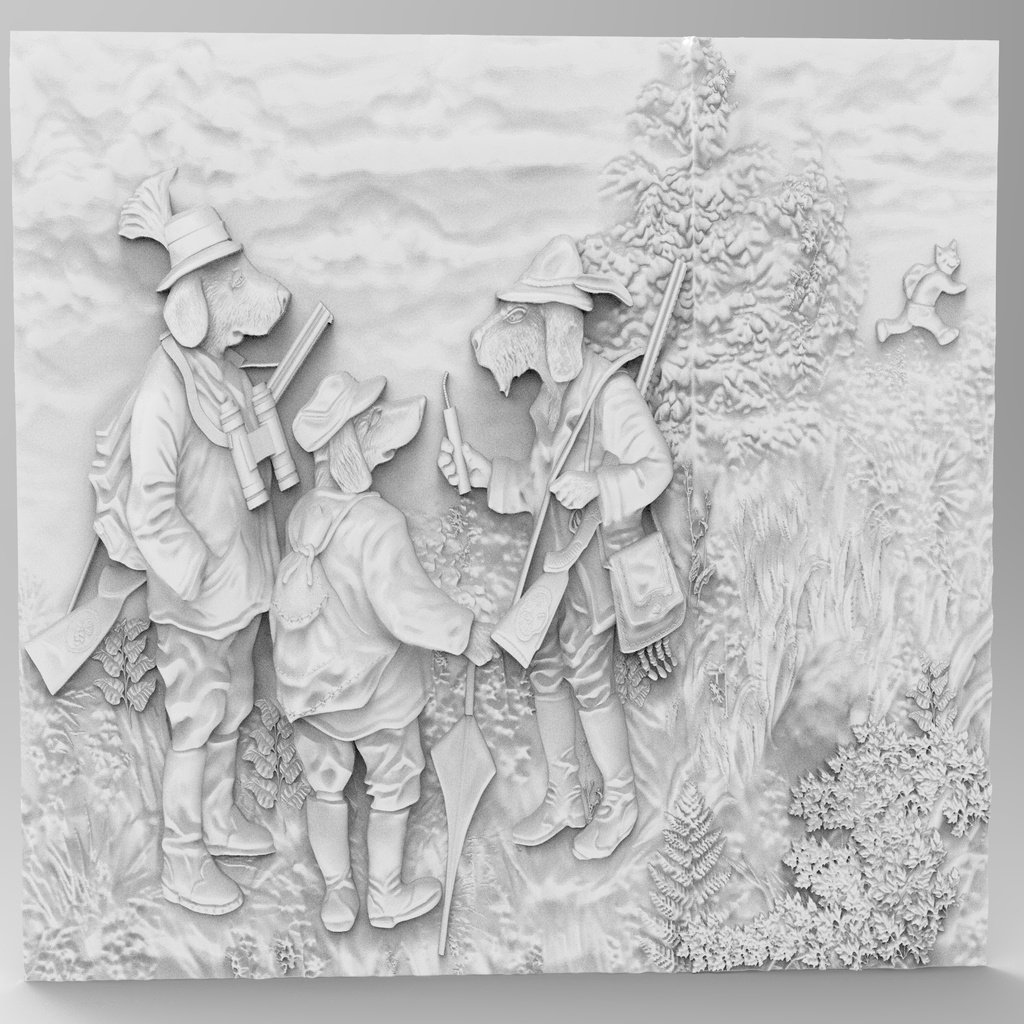

Dogs

thingiverse

Hunter Dogs Dog From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to navigationJump to search This article is about the domestic dog. For related species known as "dogs", see Canidae. For other uses, see Dog (disambiguation). Domestic dogs Temporal range: At least 14,200 years ago – present[2] Collage of Nine Dogs.jpg Selection of the different breeds of dog Conservation status Domesticated Scientific classificatione Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Canidae Genus: Canis Species: C. lupus Subspecies: C. l. familiaris[1] Trinomial name Canis lupus familiaris[1] Linnaeus, 1758 Synonyms Canis familiaris Linnaeus, 1758[3][4] Dogs show great morphological variation The domestic dog (Canis lupus familiaris when considered a subspecies of the wolf or Canis familiaris when considered a distinct species)[5] is a member of the genus Canis (canines), which forms part of the wolf-like canids,[6] and is the most widely abundant terrestrial carnivore.[7][8][9][10][11] The dog and the extant gray wolf are sister taxa[12][13][14] as modern wolves are not closely related to the wolves that were first domesticated,[13][14] which implies that the direct ancestor of the dog is extinct.[15] The dog was the first species to be domesticated[14][16] and has been selectively bred over millennia for various behaviors, sensory capabilities, and physical attributes.[17] Their long association with humans has led dogs to be uniquely attuned to human behavior[18] and they are able to thrive on a starch-rich diet that would be inadequate for other canid species.[19] Dogs vary widely in shape, size and colors.[20] They perform many roles for humans, such as hunting, herding, pulling loads, protection, assisting police and military, companionship and, more recently, aiding disabled people and therapeutic roles. This influence on human society has given them the sobriquet of "man's best friend". Contents 1 Terminology 2 Taxonomy 3 Origin 4 Biology 4.1 Anatomy 4.1.1 Size and weight 4.1.2 Senses 4.1.3 Coat 4.1.4 Tail 4.1.5 Differences from wolves 4.2 Health 4.2.1 Lifespan 4.3 Reproduction 4.3.1 Neutering 4.4 Inbreeding depression 5 Intelligence, behavior, and communication 5.1 Intelligence 5.2 Behavior 5.3 Communication 6 Ecology 6.1 Population 6.2 Competitors and predators 6.3 Diet 6.4 Range 7 Breeds 8 Roles with humans 8.1 Early roles 8.2 As pets 8.3 Work 8.4 Sports and shows 8.5 As food 8.6 Health risks to humans 8.7 Health benefits for humans 8.8 Shelters 9 Cultural depictions 9.1 Mythology and religion 9.2 Literature 9.3 Art 9.4 Education and appreciation 10 See also 10.1 Lists 11 References 12 Bibliography 13 Further reading 14 External links Terminology The term dog typically is applied both to the species (or subspecies) as a whole, and any adult male member of the same. An adult female is a bitch. An adult male capable of reproduction is a stud. An adult female capable of reproduction is a brood bitch, or brood mother. Immature males or females (that is, animals that are incapable of reproduction) are pups or puppies. A group of pups from the same gestation period is called a litter. The father of a litter is a sire. It is possible for one litter to have multiple sires. The mother of a litter is a dam. A group of any three or more adults is a pack. Hunting From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to navigationJump to search For other uses, see Hunting (disambiguation). "Hunter" redirects here. For other uses, see Hunter (disambiguation). Deer hunter on a tree stand Hunting is a practice in which a certain type of animal is killed in a certain way: the animal must be wild, it must be able to flee, the killing requires violence, and that violence must be premeditated (e.g. chasing, stalking, lying in wait). The violence must also be at the hunter's initiative (not self-defence).[1] Hunting wildlife or feral animals is most commonly done by humans for food, recreation, to remove predators that can be dangerous to humans or domestic animals, or for trade. Lawful hunting is distinguished from poaching, which is the illegal killing, trapping or capture of the hunted species. The species that are hunted are referred to as game or prey and are usually mammals and birds. Hunting arose in Homo erectus or earlier, on the order of millions of years ago. Hunting is deeply embedded in human culture. Hunting an animal for its meat can also be seen as a more natural way to obtain animal protein since regulated hunting does not cause the same environmental issues as raising domestic animals for meat, especially on factory farms. Bushmen hunter Hunting can also be a means of pest control. Hunting advocates state that hunting can be a necessary component[2] of modern wildlife management, for example, to help maintain a population of healthy animals within an environment's ecological carrying capacity when natural checks such as predators are absent or very rare.[3][4] However, the usefulness of hunting as a control measure has been questioned, and excessive hunting has also heavily contributed to the endangerment, extirpation and extinction of many animals.[5][6] The pursuit, capture and release, or capture for food of fish is called fishing, which is not commonly categorised as a form of hunting. It is also not considered hunting to pursue animals without intent to kill them, as in wildlife photography, birdwatching, or scientific research activities which involve tranquilizing or tagging of animals or birds. The practice of foraging or gathering materials from plants and mushrooms is also considered separate from hunting. Skillful tracking and acquisition of an elusive target has caused the word hunt to be used in the vernacular as a metaphor, as in treasure hunting, "bargain hunting", and even "hunting down" corruption and waste. Some animal rights activists argue that hunting is cruel, unnecessary, and unethical.[7][8] Contents 1 Etymology 2 History 2.1 Lower to Middle Paleolithic 2.2 Upper Paleolithic to Mesolithic 2.3 Neolithic and Antiquity 2.4 Pastoral and agricultural societies 2.5 Use of dog 3 Religion 3.1 Indian and Eastern religions 3.2 Christianity, Judaism, and Islam 4 National traditions 4.1 New Zealand 4.2 Shikar (Indian subcontinent) 4.3 Safari 4.4 United Kingdom 4.4.1 Shooting traditions 4.5 United States 4.5.1 Shooting 4.5.2 Regulation 4.5.3 Varmint hunting 4.5.4 Fair chase 4.5.5 Ranches 4.6 Russia 4.7 Australia 4.8 Japan 4.9 Trinidad and Tobago 5 Wildlife management 6 Laws 6.1 Right to hunt 6.2 Bag limits 6.3 Closed and open season 7 Methods 8 Statistics 8.1 Table 8.2 Graph 9 Trophy hunting 9.1 History 9.2 Conservation tool 9.3 Controversy 10 Economics 11 Environmental problems 12 Conservation 12.1 Legislation 12.1.1 Pittman–Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act of 1937 12.1.2 Federal Duck Stamp program 12.2 Species 12.2.1 Arabian oryx 12.2.2 Markhor 12.2.3 American bison 12.2.4 White rhino 12.2.5 Other species 12.3 Studies 13 Opposition to hunting 14 Hunting in the arts 15 See also 16 References 17 Further reading 18 External links Etymology The word hunt serves as both a noun ("to be on a hunt") and a verb. The noun has been dated to the early 12th century, "act of chasing game," from the verb hunt. Old English had huntung, huntoþ. The meaning of "a body of persons associated for the purpose of hunting with a pack of hounds" is first recorded in the 1570s. Meaning "the act of searching for someone or something" is from about 1600. The verb, Old English huntian "to chase game" (transitive and intransitive), perhaps developed from hunta "hunter," is related to hentan "to seize," from Proto-Germanic huntojan (the source also of Gothic hinþan "to seize, capture," Old High German hunda "booty"), which is of uncertain origin. The general sense of "search diligently" (for anything) is first recorded c. 1200.[9] History Lower to Middle Paleolithic Further information: Hunting hypothesis and Endurance running hypothesis Hunting has a long history. It pre-dates the emergence of Homo sapiens (anatomically modern humans) and may even predate genus Homo. The oldest undisputed evidence for hunting dates to the Early Pleistocene, consistent with the emergence and early dispersal of Homo erectus, about 1.7 million years ago (Acheulean).[10] While it is undisputed that Homo erectus were hunters, the importance of this for the emergence of Homo erectus from its australopithecine ancestors, including the production of stone tools and eventually the control of fire, is emphasised in the so-called "hunting hypothesis" and de-emphasised in scenarios that stress omnivory and social interaction. There is no direct evidence for hunting predating Homo erectus, in either Homo habilis or in Australopithecus. The early hominid ancestors of humans were probably frugivores or omnivores, with a partially carnivore diet from scavenging rather than hunting. Evidence for australopithecine meat consumption was presented in the 1990s.[11] It has nevertheless often been assumed that at least occasional hunting behavior may have been present well before the emergence of Homo. This can be argued on the basis of comparison with chimpanzees, the closest extant relatives of humans, who also engage in hunting, indicating that the behavioral trait may have been present in the Chimpanzee–human last common ancestor as early as 5 million years ago. The common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) regularly engages in troop predation behaviour where bands of beta males are led by an alpha male. Bonobos (Pan paniscus) have also been observed to occasionally engage in group hunting,[12] although more rarely than Pan troglodytes, mainly subsisting on a frugivorous diet.[13] Indirect evidence for Oldowan era hunting, by early Homo or late Australopithecus, has been presented in a 2009 study based on an Oldowan site in southwestern Kenya.[14] Louis Binford (1986) criticised the idea that early hominids and early humans were hunters. On the basis of the analysis of the skeletal remains of the consumed animals, he concluded that hominids and early humans were mostly scavengers, not hunters,[15] Blumenschine (1986) proposed the idea of confrontational scavenging, which involves challenging and scaring off other predators after they have made a kill, which he suggests could have been the leading method of obtaining protein-rich meat by early humans.[16] Stone spearheads dated as early as 500,000 years ago were found in South Africa.[17] Wood does not preserve well, however, and Craig Stanford, a primatologist and professor of anthropology at the University of Southern California, has suggested that the discovery of spear use by chimpanzees probably means that early humans used wooden spears as well, perhaps, five million years ago.[18] The earliest dated find of surviving wooden hunting spears dates to the very end of the Lower Paleolithic, just before 300,000 years ago. The Schöningen spears, found in 1976 in Germany, are associated with Homo heidelbergensis.[19] The hunting hypothesis sees the emergence of behavioral modernity in the Middle Paleolithic as directly related to hunting, including mating behaviour, the establishment of language, culture, and religion, mythology and animal sacrifice. Upper Paleolithic to Mesolithic Main article: Hunter-gatherers Saharan rock art with prehistoric archers Inuit walrus hunters, 1999 Evidence exists that hunting may have been one of the multiple environmental factors leading to the Holocene extinction of megafauna and their replacement by smaller herbivores.[20] North American megafauna extinction was coincidental with the Younger Dryas impact event, possibly making hunting a less critical factor in prehistoric species loss than had been previously thought.[21] However, in other locations such as Australia, humans are thought to have played a very significant role in the extinction of the Australian megafauna that was widespread prior to human occupation.[22][23] Hunting was a crucial component of hunter-gatherer societies before the domestication of livestock and the dawn of agriculture, beginning about 11,000 years ago in some parts of the world. In addition to the spear, hunting weapons developed during the Upper Paleolithic include the atlatl (a spear-thrower; before 30,000 years ago) and the bow (18,000 years ago). By the Mesolithic, hunting strategies had diversified with the development of these more far-reaching weapons and the domestication of the dog about 15,000 years ago. Evidence puts the earliest known mammoth hunting in Asia with spears to approximately 16,200 years ago.[24] Sharp flint piece from Bjerlev Hede in central Jutland. Dated around 12,500 BC and considered the oldest hunting tool from Denmark Many species of animals have been hunted throughout history. It has been suggested that in North America and Eurasia, caribou and wild reindeer "may well be the species of single greatest importance in the entire anthropological literature on hunting"[25] (see also Reindeer Age), although the varying importance of different species depended on the geographic location. Ancient Greek black-figure pottery depicting the return of a hunter and his dog; made in Athens c. 540 BC, found in Rhodes Mesolithic hunter-gathering lifestyles remained prevalent in some parts of the Americas, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Siberia, as well as all of Australia, until the European Age of Discovery. They still persist in some tribal societies, albeit in rapid decline. Peoples that preserved Paleolithic hunting-gathering until the recent past include some indigenous peoples of the Amazonas (Aché), some Central and Southern African (San people), some peoples of New Guinea (Fayu), the Mlabri of Thailand and Laos, the Vedda people of Sri Lanka, and a handful of uncontacted peoples. In Africa, one of the last remaining hunter-gatherer tribes are the Hadza of Tanzania.[26] Neolithic and Antiquity Artemis with a Hind, a Roman copy of an Ancient Greek sculpture, c. 325 BC, by Leochares An example of a Goguryeo tomb mural of hunting, middle of the first millennium Even as animal domestication became relatively widespread and after the development of agriculture, hunting was usually a significant contributor to the human food supply. The supplementary meat and materials from hunting included protein, bone for implements, sinew for cordage, fur, feathers, rawhide and leather used in clothing. Hunting is still vital in marginal climates, especially those unsuited for pastoral uses or agriculture.[27] For example, Inuit people in the Arctic trap and hunt animals for clothing and use the skins of sea mammals to make kayaks, clothing, and footwear. On ancient reliefs, especially from Mesopotamia, kings are often depicted as hunters of big game such as lions and are often portrayed hunting from a war chariot. The cultural and psychological importance of hunting in ancient societies is represented by deities such as the horned god Cernunnos and lunar goddesses of classical antiquity, the Greek Artemis or Roman Diana. Taboos are often related to hunting, and mythological association of prey species with a divinity could be reflected in hunting restrictions such as a reserve surrounding a temple. Euripides' tale of Artemis and Actaeon, for example, may be seen as a caution against disrespect of prey or impudent boasting. With the domestication of the dog, birds of prey, and the ferret, various forms of animal-aided hunting developed, including venery (scent hound hunting, such as fox hunting), coursing (sight hound hunting), falconry, and ferreting. While these are all associated with medieval hunting, over time, various dog breeds were selected for very precise tasks during the hunt, reflected in such names as pointer and setter. See also: Lion hunting

With this file you will be able to print Dogs with your 3D printer. Click on the button and save the file on your computer to work, edit or customize your design. You can also find more 3D designs for printers on Dogs.