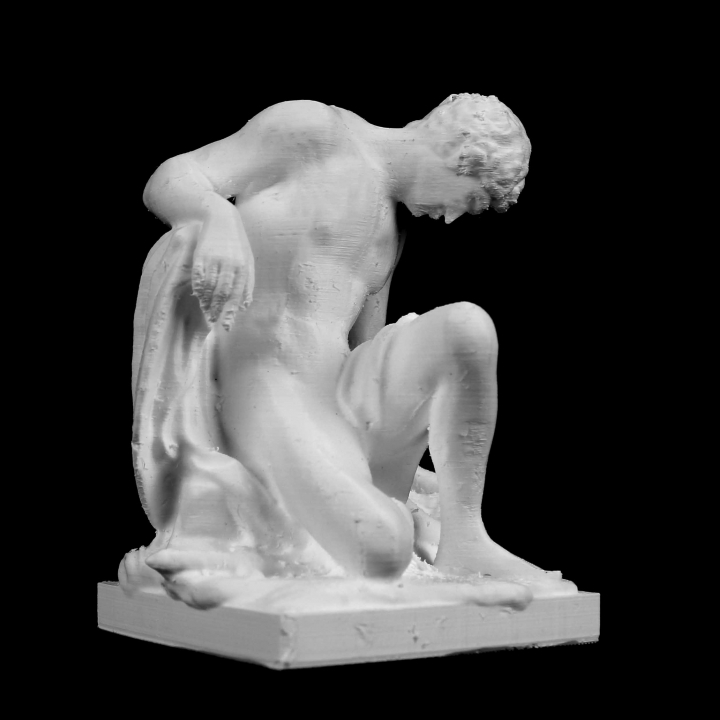

Dying Gladiator at The Louvre, Paris

myminifactory

A mortally wounded gladiator, facing death with grace and dignity, is contemplating the laurel crown he was awarded for his courage. This was Pierre Julien’s second admission piece for the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture and a crucial work for him. He had presented another piece for admission in 1776, a statue of Ganymede (Louvre) and had been refused, possibly due to his teacher, Guillaume II Coustou’s, lack of support for his too talented pupil. Humiliated by this unjust failure, Julien had thought of becoming a naval sculptor but, encouraged by friends, persevered and presented Dying Gladiator to the Académie in 1778. He was admitted on 27 March 1779 and appointed an assistant teacher in 1781. Acclaim for the sculpture at the 1779 Salon made amends for the affront of 1776. In this scholarly work, the artist demonstrated his mastery of academic criteria whilst asserting personal qualities. The statue is a proclamation of his knowledge of antique sculpture. He was reinterpreting the Dying Gladiator in the Capitoline Museum in Rome, a marble copy of which he had sculpted during his stay at the Académie de France in Rome from 1769 to 1772. The pose of the legs seems to have been inspired by the famous antique sculpture The Knife Grinder in Florence, a marble copy of which was executed by the Italian Foggini in 1684 for Versailles (now in the Louvre). Julien’s nude gladiator demonstrates his complete mastery of anatomy, and also drapery at the rear of the statue. But it was the sculptor’s personal contribution which imbues the work with its sensitivity: the elegant proportions, unctuous modelling and delicate execution (the finesse of the hands, laurel leaves and strands of hair), the marble’s perfect finish and the rendering of textures (the polish of the shield and sword suggest their metallic brilliance). The work is a dazzling testimony to the renaissance of classical sensibility, albeit in a codified genre. The return to antiquity and nature, begun in the 1740s by the sculptors Edme Bouchardon and Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, asserted itself in the 1770s. Julien was exalting the heroism of a man overcoming his pain and stoically dying in silence. The balanced composition, dignified pose, discreet chest wound and restrained expression are formal echoes of this heroic serenity. Like the Laocoon, one of the most admired antique statues at that time, the gladiator is in agony but not crying out in pain, and it is this dignity in suffering which makes the figure more sensitive and inward-looking. A critic at the 1779 Salon conveyed our empathy: “He is a wretched soul expiring, whose pain we share, in short, this figure is all soul.” This object is part of "Scan The World". Scan the World is a non-profit initiative introduced by MyMiniFactory, through which we are creating a digital archive of fully 3D printable sculptures, artworks and landmarks from across the globe for the public to access for free. Scan the World is an open source, community effort, if you have interesting items around you and would like to contribute, email stw@myminifactory.com to find out how you can help.

With this file you will be able to print Dying Gladiator at The Louvre, Paris with your 3D printer. Click on the button and save the file on your computer to work, edit or customize your design. You can also find more 3D designs for printers on Dying Gladiator at The Louvre, Paris.