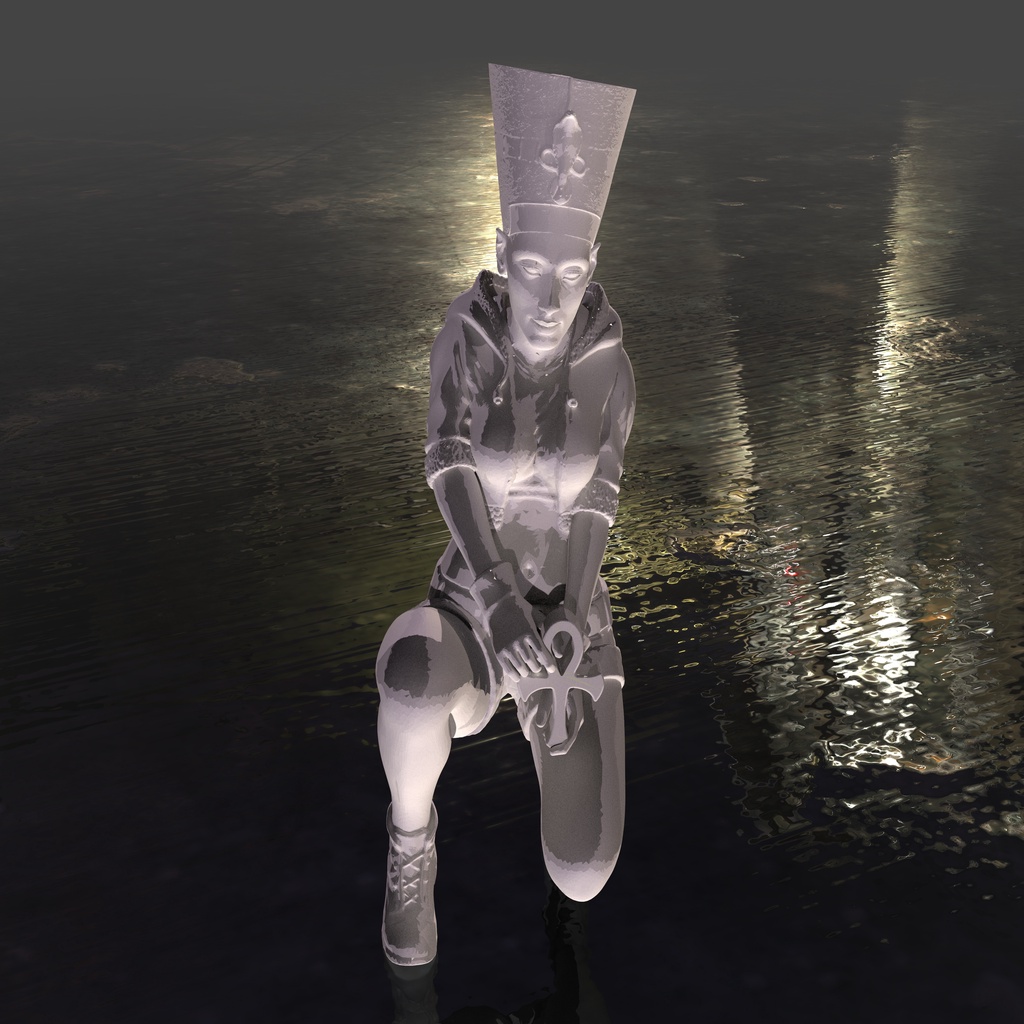

Modern Nefertiti, sitting full body

thingiverse

Nefertiti From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to navigationJump to search This article is about the Ancient Egyptian Queen Nefertiti. For other uses, see Nefertiti (disambiguation). For other individuals named Neferneferuaten, see Neferneferuaten (disambiguation). Nefertiti Nofretete Neues Museum.jpg The bust of Nefertiti from the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection, presently in the Neues Museum. Queen consort of Egypt Tenure 1353–1336 BC[1] or 1351–1334 BC[2] Born c. 1370 BC Thebes Died c. 1330 BC Spouse Akhenaten Issue Meritaten Meketaten Ankhesenamun Neferneferuaten Tasherit Neferneferure Setepenre Full name Neferneferuaten Nefertiti Dynasty 18th of Egypt Father Ay (possibly) Mother Iuy? (possibly) Religion Ancient Egyptian religion Neferneferuaten-Nefertiti in hieroglyphs X1 N35 N5 M17 F35 F35 F35 F35 F35 M18 X1 Z4 B1 Neferneferuaten Nefertiti Nfr nfrw itn Nfr.t jy.tj Beautiful are the Beauties of Aten, the Beautiful one has come Great Royal Wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten Neferneferuaten Nefertiti (/ˌnɛfərˈtiːti/[3]) (c. 1370 – c. 1330 BC) was an Egyptian queen and the Great Royal Wife (chief consort) of Akhenaten, an Egyptian Pharaoh. Nefertiti and her husband were known for a religious revolution, in which they worshiped one god only, Aten, or the sun disc. With her husband, she reigned at what was arguably the wealthiest period of Ancient Egyptian history.[4] Some scholars believe that Nefertiti ruled briefly as Neferneferuaten after her husband's death and before the accession of Tutankhamun, although this identification is a matter of ongoing debate.[5][6] If Nefertiti did rule as Pharaoh, her reign was marked by the fall of Amarna and relocation of the capital back to the traditional city of Thebes.[7] Nefertiti had many titles including Hereditary Princess (iryt-p`t); Great of Praises (wrt-Hzwt); Lady of Grace (nbt-im3t), Sweet of Love (bnrt-mrwt); Lady of The Two Lands (nbt-t3wy); Main King's Wife, his beloved (Hmt-nswt-‘3t mryt.f); Great King's Wife, his beloved (Hmt-nswt-wrt mryt.f), Lady of all Women (Hnwt-Hmwt-nbwt); and Mistress of Upper and Lower Egypt (Hnwt-Shm’w-mhw).[8] She was made famous by her bust, now in Berlin's Neues Museum. The bust is one of the most copied works of ancient Egypt. It was attributed to the sculptor Thutmose, and it was found in his workshop. Contents 1 Family 2 Life 2.1 Possible reign as Pharaoh 3 Death 3.1 Old theories 3.2 New theories 4 Burial 4.1 "The Younger Lady" 5 Hittite letters 6 In the arts 6.1 Film 6.2 Video Games 6.3 Literature 6.4 Music 6.5 Television 7 Gallery 8 References 8.1 Works cited 9 External links Family See also: Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt family tree Limestone column fragment showing a cartouche of Nefertiti. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London A "house altar" depicting Akhenaten, Nefertiti and three of their daughters; limestone; New Kingdom, Amarna period, 18th dynasty; c. 1350 BC. Collection: Ägyptisches Museum Berlin, Inv. 14145 Nefertiti's name, Egyptian Nfr.t-jy.tj, can be translated as "The Beautiful Woman has Come".[9] Nefertiti's parentage is not known with certainty, but one often cited theory is that she was the daughter of Ay, later to be pharaoh.[9] One major problem of this theory is that neither Ay nor his wife Tey are explicitly called the father and mother of Nefertiti in existing sources. In fact, Tey's only connection with her was that she was the "nurse of the great queen" Nefertiti, an unlikely title for a queen's mother.[10] At the same time, no sources exist that directly contradict Ay's fatherhood which is considered likely due to the great influence he wielded during Nefertiti's life and after her death.[9] To solve this problem, it has been proposed that Ay had another wife before Tey, namely Iuy, whose existence and connection to Ay is suggested by some evidence. According to this theory, Nefertiti was the daughter of Ay and Iuy, but her mother died before her rise to queen, whereupon Ay married Tey, making her Nefertiti's step-mother. Nevertheless, this entire proposal is based on speculation and conjecture.[11] It has also been proposed that Nefertiti was Akhenaten's full sister, though this is contradicted by her titles which do not include those usually used by the daughters of a Pharaoh.[9] Another theory about her parenthood that gained some support identified Nefertiti with the Mitanni princess Tadukhipa,[12] partially based on Nefertiti's name ("The Beautiful Woman has Come") which has been interpreted by some scholars as signifying a foreign origin.[9] However, Tadukhipa was already married to Akhenaten's father and there is no evidence for any reason why this woman would need to alter her name in a proposed marriage to Akhenaten or any hard evidence of a foreign non-Egyptian background for Nefertiti. Nefertiti's scenes in the tombs of the nobles in Amarna mention the queen's sister who is named Mutbenret (previously read as Mutnodjemet).[13][14] The exact dates when Nefertiti married Akhenaten and became the king's great royal wife of Egypt are uncertain. Their six known daughters (and estimated years of birth) were:[14][12] Meritaten: No later than year 1, possibly later became Pharaoh Neferneferuaten. Meketaten: Year 4. Ankhesenpaaten, also known as Ankhesenamun, later queen of Tutankhamun Neferneferuaten Tasherit: Year 8, possibly later became Pharaoh Neferneferuaten. Neferneferure: Year 9. Setepenre: Year 11. Life Alabaster sunken relief depicting Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and daughter Meritaten. Early Aten cartouches on king's arm and chest. From Amarna, Egypt. 18th Dynasty. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London Close-up of a limestone relief depicting Nefertiti smiting a female captive on a royal barge. On display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Nefertiti first appears in scenes in Thebes. In the damaged tomb (TT188) of the royal butler Parennefer, the new king Amenhotep IV is accompanied by a royal woman, and this lady is thought to be an early depiction of Nefertiti. The king and queen are shown worshiping the Aten. In the tomb of the vizier Ramose, Nefertiti is shown standing behind Amenhotep IV in the Window of Appearance during the reward ceremony for the vizier.[12] A standing/striding figure of Nefertiti made of limestone. Originally from Amarna, part of the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection. During the early years in Thebes, Akhenaten (still known as Amenhotep IV) had several temples erected at Karnak. One of the structures, the Mansion of the Benben (hwt-ben-ben), was dedicated to Nefertiti. She is depicted with her daughter Meritaten and in some scenes the princess Meketaten participates as well. In scenes found on the talatat, Nefertiti appears almost twice as often as her husband. She is shown appearing behind her husband the Pharaoh in offering scenes in the role of the queen supporting her husband, but she is also depicted in scenes that would have normally been the prerogative of the king. She is shown smiting the enemy, and captive enemies decorate her throne.[15] In the fourth year of his reign, Amenhotep IV decided to move the capital to Akhetaten (modern Amarna). In his fifth year, Amenhotep IV officially changed his name to Akhenaten, and Nefertiti was henceforth known as Neferneferuaten-Nefertiti. The name change was a sign of the ever-increasing importance of the cult of the Aten. It changed Egypt's religion from a polytheistic religion to a religion which may have been better described as a monolatry (the depiction of a single god as an object for worship) or henotheism (one god, who is not the only god).[16] The boundary stelae of years 4 and 5 mark the boundaries of the new city and suggest that the move to the new city of Akhetaten occurred around that time. The new city contained several large open-air temples dedicated to the Aten. Nefertiti and her family would have resided in the Great Royal Palace in the centre of the city and possibly at the Northern Palace as well. Nefertiti and the rest of the royal family feature prominently in the scenes at the palaces and in the tombs of the nobles. Nefertiti's steward during this time was an official named Meryre II. He would have been in charge of running her household.[5][12] Inscriptions in the tombs of Huya and Meryre II dated to Year 12, 2nd month of Peret, Day 8 show a large foreign tribute. The people of Kharu (the north) and Kush (the south) are shown bringing gifts of gold and precious items to Akhenaten and Nefertiti. In the tomb of Meryre II, Nefertiti's steward, the royal couple is shown seated in a kiosk with their six daughters in attendance.[5][12] This is one of the last times princess Meketaten is shown alive. Two representations of Nefertiti that were excavated by Flinders Petrie appear to show Nefertiti in the middle to later part of Akhenaten's reign 'after the exaggerated style of the early years had relaxed somewhat'.[17] One is a small piece on limestone and is a preliminary sketch of Nefertiti wearing her distinctive tall crown with carving began around the mouth, chin, ear and tab of the crown. Another is a small inlay head (Petrie Museum Number UC103) modeled from reddish-brown quartzite that was clearly intended to fit into a larger composition. Meketaten may have died in year 13 or 14. Nefertiti, Akhenaten, and three princesses are shown mourning her.[18] Nefertiti disappears from the record soon after that.[12] Possible reign as Pharaoh Main article: Neferneferuaten Many scholars believe Nefertiti had a role elevated from that of Great Royal Wife, and was promoted to co-regent by her husband Pharaoh Akhenaten before his death.[19] She is depicted in many archaeological sites as equal in stature to a King, smiting Egypt's enemies, riding a chariot, and worshipping the Aten in the manner of a Pharaoh.[20] When Nefertiti's name disappears from historical records, it is replaced by that of a co-regent named Neferneferuaten, who became a female Pharaoh.[21] It seems likely that Nefertiti, in a similar fashion to the previous female Pharaoh Hatshepsut, assumed the kingship under the name Pharaoh Neferneferuaten after her husband's death. It is also possible that, in a similar fashion to Hatshepsut, Nefertiti disguised herself as a male and assumed the male alter-ego of Smenkhkare; in this instance she could have elevated her daughter Meritaten to the role of Great Royal Wife. If Nefertiti did rule Egypt as Pharaoh, it has been theorized that she would have attempted damage control and may have re-instated the Ancient Egyptian religion and the Amun priests, and had Tutankhamun raised in with the traditional gods.[22] Archaeologist and Egyptologist Dr. Zahi Hawass theorized that Nefertiti returned to Thebes from Amarna to rule as Pharaoh, based on ushabti and other feminine evidence of a female Pharaoh found in Tutankhamun's tomb, as well as evidence of Nefertiti smiting Egypt's enemies which was a duty reserved to kings.[23] Death Further information: Amarna succession Nefertiti worshipping the Aten. She is given the title of Mistress of the Two Lands. On display at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Old theories Fragment with cartouche of Akhenaten, which is followed by epithet Great in his Lifespan and the title of Nefertiti Great King's Wife. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London Pre-2012 Egyptological theories thought that Nefertiti vanished from the historical record around Year 12 of Akhenaten's reign, with no word of her thereafter. Explanations included a sudden death, by a plague that was sweeping through the city, or some other natural death. This theory was based on the discovery of several ushabti fragments inscribed for Nefertiti (now located in the Louvre and Brooklyn Museums). A previous theory, that she fell into disgrace, was discredited when deliberate erasures of monuments belonging to a queen of Akhenaten were shown to refer to Kiya instead.[14] During Akhenaten's reign (and perhaps after), Nefertiti enjoyed unprecedented power. By the twelfth year of his reign, there is evidence she may have been elevated to the status of co-regent:[24] equal in status to the pharaoh — as may be depicted on the Coregency Stela. It is possible Nefertiti is the ruler named Neferneferuaten. Some theories believe that Nefertiti was still alive and held influence on the younger royals. If this is the case, that influence and presumably Nefertiti's own life would have ended by year 3 of Tutankhaten's reign (1331 BC). In that year, Tutankhaten changed his name to Tutankhamun. This is evidence of his return to the official worship of Amun, and abandonment of Amarna to return the capital to Thebes.[5] New theories In 2012, an inscription dated to Year 16, month 3 of Akhet, day 15 of the reign of Akhenaten was discovered in a limestone quarry at Dayr Abū Ḥinnis, about 10 kilometres north of Amarna.[25] It was discovered within Quarry 320 in the largest wadi.[26] The five line inscription, written in red ochre, mentions of the presence of the “Great Royal Wife, His Beloved, Mistress of the Two Lands, Neferneferuaten Nefertiti”.[27][28] The final line of the inscription refers to ongoing building work being carried out under the authority of the king's scribe Penthu[28] on the Small Aten Temple in Amarna.[29] Van der Perre stresses that:[30] This inscription offers incontrovertible evidence that both Akhenaten and Nefertiti were still alive in the 16th year of his [Akhenaten's] reign and, more importantly, that they were still holding the same positions as at the start of their reign. This makes it necessary to rethink the final years of the Amarna Period. This means that Nefertiti was alive in the second to last year of Akhenaten's reign, (this pharaoh's highest attested regnal year was his Year 17) and demonstrates that Akhenaten still ruled alone, with his wife by his side. Therefore, the rule of the female Amarna pharaoh known as Neferneferuaten must be placed between the death of Akhenaten and the accession of Tutankhamun. This female pharaoh used the epithet 'Effective for her husband' in one of her cartouches,[31] which means she was either Nefertiti or her daughter Meritaten (who was married to king Smenkhkare). Burial Limestone trial piece showing head of Nefertiti. Mainly in ink, but the lips were cut out. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London Nefertiti's burial was intended to be made within the Royal Tomb as laid out in the Boundary Stelae.[32] It is possible that the unfinished annex of the Royal Tomb was intended for her use.[33] However, given that Akhenaten appears to have predeceased her it is highly unlikely she was ever buried there. One shabti is known to have been made for her.[34] The unfinished Tomb 29, which would have been of very similar dimensions to the Royal Tomb had it been finished, is the most likely candidate for a tomb begun for Nefertiti's exclusive use.[35] Given that it lacks a burial chamber, she was not interred there either. In 2015, English archaeologist Nicholas Reeves announced that he had discovered evidence in high resolution scans of Tutankhamun's tomb "indications of two previously unknown doorways, one set within a larger partition wall and both seemingly untouched since antiquity ... To the north [there] appears to be signaled a continuation of tomb KV62, and within these uncharted depths an earlier royal interment – that of Nefertiti herself."[36] Radar scans conducted in November 2015 by Japanese radar expert Hirokatsu Watanabe seemed to confirm Reeves' theory that there were likely voids behind the northern and westerns walls of Tutankhamun's burial chamber.[37] A second radar scan could not replicate Watanabe's results. A third radar scan has eliminated the possibility that there are any hidden chambers.[38] The positive findings of the first GPR scan were likely a result of 'ghost' reflections of the signal from the walls.[39] In 1898, French archeologist Victor Loret found two female mummies among those cached inside the tomb of Amenhotep II in KV35 in the Valley of the Kings. These two mummies, known as the 'The Elder Lady' and 'The Younger Lady', were identified as likely candidates of her remains. An article in KMT magazine in 2001 suggested that the Elder Lady may be Nefertiti's body.[40] It was argued that the evidence suggests that the mummy is around her mid-thirties or early forties, Nefertiti's guessed age of death. More evidence to support this identification was that the mummy's teeth look like that of a 29- to 38-year-old, Nefertiti's most likely age of death. Also, unfinished busts of Nefertiti appear to resemble the mummy's face, though other suggestions included Ankhesenamun. However, it eventually became apparent that the 'Elder Lady' is in fact Queen Tiye, mother of Akhenaten. A lock of hair found in a coffinette bearing an inscription naming Queen Tiye proved a near perfect match to the hair of the 'ELder Lady'.[41] DNA analysis has revealed that she was the daughter of Yuya and Thuya, who were the parents of Queen Tiye, thus ruling her out as Nefertiti.[42] "The Younger Lady" Main article: The Younger Lady On June 9, 2003, archaeologist Joann Fletcher, a specialist in ancient hair from the University of York in England, announced that Nefertiti's mummy may have been the Younger Lady. Fletcher suggested that Nefertiti was the Pharaoh Smenkhkare. Some Egyptologists hold to this view though the majority believe Smenkhkare to have been a separate person. Fletcher led an expedition funded by the Discovery Channel to examine what they believed to have been Nefertiti's mummy. However, an independent researcher, Marianne Luban, had previously suggested that the KV35 Younger Lady could be Nefertiti in an online article, "Do We Have the Mummy of Nefertiti?" published in 1999.[43] The team claimed that the mummy they examined was damaged in a way suggesting the body had been deliberately desecrated in antiquity. Mummification techniques, such as the use of embalming fluid and the presence of an intact brain, suggested an eighteenth-dynasty royal mummy. Other elements which the team used to support their theory were the age of the body, the presence of embedded nefer beads, and a wig of a rare style worn by Nefertiti. They further claimed that the mummy's arm was originally bent in the position reserved for pharaohs, but was later snapped off and replaced with another arm in a normal position. Most Egyptologists, among them Kent Weeks and Peter Lacovara, generally dismiss Fletcher's claims as unsubstantiated. They say that ancient mummies are almost impossible to identify as a particular person without DNA. As bodies of Nefertiti's parents or children have never been identified, her conclusive identification is impossible. Any circumstantial evidence, such as hairstyle and arm position, is not reliable enough to pinpoint a single, specific historical person. The cause of damage to the mummy can only be speculated upon, and the alleged revenge is an unsubstantiated theory. Bent arms, contrary to Fletcher's claims, were not reserved to pharaohs; this was also used for other members of the royal family. The wig found near the mummy is of unknown origin, and cannot be conclusively linked to that specific body. Finally, the 18th dynasty was one of the largest and most prosperous dynasties of ancient Egypt. A female royal mummy could be any of a hundred royal wives or daughters from the 18th dynasty's more than 200 years on the throne. In addition to that, there was controversy about both the age and sex of the mummy. On June 12, 2003, Egyptian archaeologist Dr. Zahi Hawass, head of Egypt's Supreme Council for Antiquities, also dismissed the claim, citing insufficient evidence. On August 30, 2003, Reuters further quoted Hawass: "I'm sure that this mummy is not a female", and "Dr Fletcher has broken the rules and therefore, at least until we have reviewed the situation with her university, she must be banned from working in Egypt."[44] On different occasions, Hawass has claimed that the mummy is female and male.[45] In a more recent research effort led by Hawass, the mummy was put through CT scan analysis and DNA analysis. Researchers concluded that she is Tutankhamun's biological mother, an unnamed daughter of Amenhotep III and Tiye, not Nefertiti.[46] Fragments of shattered bone were found in the sinus. The theory that the damage to the left side of the face was inflicted post-mummification was rejected as undamaged embalming packs were placed over top of the affected area.[47] The broken-off bent forearm found near the mummy, which had been proposed to have belonged to it, was conclusively shown not to actually belong to the Younger Lady.[48] Hittite letters A document was found in the ancient Hittite capital of Hattusa which dates to the Amarna period; the so-called "Deeds" of Suppiluliuma I. The Hittite ruler receives a letter from the Egyptian queen, while being in siege on Karkemish. The letter reads:[49] My husband has died and I have no son. They say about you that you have many sons. You might give me one of your sons to become my husband. I would not wish to take one of my subjects as a husband... I am afraid. This proposal is considered extraordinary as New Kingdom royal women never married foreign royalty.[50] Suppiluliuma I was understandably surprised and exclaimed to his courtiers:[51] Nothing like this has happened to me in my entire life! Understandably, he was wary, and had an envoy investigate the situation, but by so doing, he missed his chance to bring Egypt into his empire. He eventually did send one of his sons, Zannanza, but the prince died, perhaps murdered, en route.[52] The identity of the queen who wrote the letter is uncertain. She is called Dakhamunzu in the Hittite annals, a possible translation of the Egyptian title Tahemetnesu (The King's Wife).[53] The possible candidates are Nefertiti, Meritaten,[54] and Ankhesenamun. Ankhesenamun once seemed likely since there were no candidates for the throne on the death of her husband, Tutankhamun, whereas Akhenaten had at least two legitimate successors.[49] but this was based on a 27-year reign for the last 18th dynasty pharaoh Horemheb who is now accepted to have had a shorter reign of only 14 years. This makes the deceased Egyptian king appear to be Akhenaten instead rather than Tutankhamun. Furthermore, the phrase regarding marriage to 'one of my subjects' (translated by some as 'servants') is possibly either a reference to the Grand Vizier Ay or a secondary member of the Egyptian royal family line. Since Nefertiti was depicted as being as powerful as her husband in official monuments smiting Egypt's enemies, she might be the Dakhamunzu in the Amarna correspondence as Nicholas Reeves believes.[55] In the arts This article appears to contain trivial, minor, or unrelated references to popular culture. Please reorganize this content to explain the subject's impact on popular culture, using references to reliable sources, rather than simply listing appearances. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2017) Portrait study of Nefertiti Bust of Nefertiti in the flag of the Minya Governorate, Egypt Film In The Egyptian (1954), Nefertiti is played by Anitra Stevens. In Nefertiti, Queen of the Nile (1961), Nefertiti is played by Jeanne Crain. In Nefertiti, figlia del sole (1994), Nefertiti is played by Michela Rocco di Torrepadula. In musical mini-film Remember the Time (1992), Nefertiti is played by Iman. Video Games In Assassins Creed Origins, Nefertiti features as an enemy in "The Curse of the Pharaohs" DLC who must be defeated so that she may finally rest in peace, her curse on the city of Thebes being removed[56][57]. Literature (Alphabetical by author's last name) A God Against the Gods (1976) and Return to Thebes (1977) by Allen Drury chronicle the story of Akhenaten and Nefertiti. In Akhenaten, Dweller in Truth (1985) by Naguib Mahfouz, Nefertiti is one of the characters who reflects on Akhenaten and the Amarna period. Nefertiti: A Novel (2008), by Michelle Moran The fourth section of James Rollins' sixth Sigma Force novel, The Doomsday Key (2009), is titled The Dark Madonna, and throughout the book the characters piece together Egyptian, pagan, and Christian myths, theology, and facts to find the Doomsday Key and Saint Malachy's original and complete book of Doomsday Prophecies. They ultimately find the key in a canopic jar, held by a preserved body in a glass casket bearing the inscription: "Here lies Meritaten, daughter of King Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti. She who crossed the seas and brought the sun god Ra to these cold lands".[58] The Egyptian (1945) is an historical novel by Mika Waltari. Music Nefertiti, the Beautiful One Has Come (1962), a live album by American jazz pianist Cecil Taylor. Nefertiti (1967), a studio album by American jazz trumpeter Miles Davis. Nefertiti (1976), a studio album by American jazz pianist Andrew Hill. Nefertiti (2014), a classical ballet by American composer John Craton. African Queens (Ritchie Family, 1978 disco album): Nefertiti is mentioned as part of a concept album regarding three famous African queens: Nefertiti, Cleopatra and the Queen of Sheba. Each Queen gets her own story verse in the course 18 minute medley. The song "Q.U.E.E.N." by Janelle Monáe from her album The Electric Lady (2013) mentions Nefertiti. The lyric is "My crown too heavy like the Queen Nefertiti". Rihanna paid homage to Nefertiti on the cover of Vogue Arabia in November 2018.[59] On both weekends of Coachella 2018, Beyoncé referenced Nefertiti in her opening outfits, as well as Egyptian culture throughout the performance.[60] Television In Prophet Joseph (2008), Nefertiti is played by Leila Boloukat In Doctor Who, "Dinosaurs on a Spaceship" (2012), Nefertiti is played by Riann Steele In The Loretta Young Show, "Queen Nefertiti" (6 Jan. 1957, alternate title "Letter to Loretta"), Nefertiti is played by Loretta Young In "City of the Dead" in Hercules: The Legendary Journeys, Nefertiti is played by Gabriella Larkin.[61] Gallery Headless bust of Akhenaten or Nefertiti. Part of a composite red quartzite statue. Intentional damage. Four pairs of early Aten cartouches. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London Limestone statuette of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, or Amenhotep III and Tiye,[62] and a princess. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London Limestone relief fragment. A princess holding sistrum behind Nefertiti, who is partially seen. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London Siliceous limestone fragment relief of Nefertiti. Extreme style of portrait. Reign of Akhenaten, probably early Amarna Period. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London Granite head statue of Nefertiti. The securing post at head apex allows for different hairstyles to adorn the head. Altes Museum, Berlin. Head statue of Nefertiti, Altes Museum, Berlin. Akhenaten, Nefertiti and their daughters before the Aten. Stela of Akhenaten and his family, Egyptian Museum, Cairo. Nefertiti offering oil to the Aten. Brooklyn Museum. Talatat showing Nefertiti worshipping the Aten. Altes Museum. Relief fragment with Nefertiti, Brooklyn Museum. Akhenaten and Nefertiti. Louvre Museum, Paris. Nefertiti presenting an image of the goddess Maat to the Aten. Brooklyn Museum. Talatat representing Nefertiti and Akhenaten worshipping the Aten. Royal Ontario Museum. Boundary stele of Amarna with Nefertiti and her daughter, princess Meketaten, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Limestone relief of Nefertiti kissing one of her daughters, Brooklyn Museum. Talatat with an aged Nefertiti, Brooklyn Museum. This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (July 2015) This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2013) Not to be confused with informal attire. For other uses, see Casual (disambiguation). Museo del Bicentenario - Galera de Roberto M. Ortiz.jpg Part of a series on Western dress codes and corresponding attires Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Phillip sit on thrones before a full Parliament.jpg Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip at formal opening of the Parliament of Canada (1957) Formal (full dress)[show] Semi-formal (half dress)[show] Informal (undress, "dress clothes")[show] Casual (anything not above)[show] Supplementary alternatives[show] Legend: Emoji u2600.svg = Day (before 6 p.m.) Emoji u1f319.svg = Evening (after 6 p.m.) = Bow tie colour Female symbol.svg = Ladies BathingSuit1920s.jpg Fashion portal Portal-puzzle.svg Contents/Culture and the arts portal vte Casual wear/attire/clothing is a Western dress code category that comprises anything not traditionally appropriate with more formal dress codes: formal wear, semi-formal wear, or informal wear. It saw broadscale introduction in the Western world following the counterculture of the 1960s. In general, casual wear is associated with emphasising personal comfort and individuality over formality or conformity. As such, it may referred to as leisurewear. In a broader sense, the word "casual" may be defined as anything relaxed, occasional, spontaneous, "suited for everyday use", or "informal" in the sense of "not formal" (although notably informal attire actually traditionally refers to a Western dress code more formal than casual attire, a step below semi-formal attire).[1] Contents 1 Definition of casual: what it is not 2 Overview 3 Men 4 Women 5 Gallery 6 See also 7 References Definition of casual: what it is not In essence, because of its wide variety of interpretations, casual wear may be defined not by what it is but rather by what it is not: Formal wear, such as: Morning dress White tie (dress coat) but also ceremonial dress variants, including: Court uniforms Full dress uniform (military) Religious clothing Folk costumes Academic clothing Semi-formal wear, such as: Black lounge suit Black tie (tuxedo) Informal attire, such as: Suits, including dress shirts, neckties, waistcoats and dress shoes[2] Yet, when indicated as a dress code for instance on an invitation to a gathering or in an office place, casual wear may still be expected to be done tastefully, meaning that trousers and shirts do not have holes, tears, or stains. [3] , it may also be combined with informal wear dress code components, illustrated by dress codes such as business casual, smart casual . Furthermore, dress codes within casual wear category such as business casual, smart casual or casual Friday may indicate expectation of some sartorial effort, including suit jacket, dress trousers, and necktie, resembling the result of informal attire. Overview With the popularity of spectator sports in the late 20th century, a good deal of athletic gear has influenced casual wear, such as jogging suits, running shoes, and track clothing. Work wear worn for manual labor also falls into casual wear. Basic materials used for casual wear include denim, cotton, jersey, flannel, and fleece. Materials such as velvet, chiffon, and brocade are often associated with more formal cloths.[4] While utilitarian costume comes to mind first for casual dress, however, there is also a wide range of flamboyance and theatricality. Punk fashion and fashion of the 1970s and 1980s is a striking example. Madonna introduced a great deal of lace, jewelry, and cosmetics into casual wear during the 1980s. In the 1990s, hip hop fashion played up elaborate jewelry and luxurious materials worn in conjunction with athletic gear and the clothing of manual labor. Men Sport coat, blazer, jeans, dress shirt (casually turn down collared), and a T-shirt describe to be typically casual wear for men in the 21st century.[5][6] Women Casual wear is typically the dress code in which forms of gender expression are experimented with. An obvious example is masculine jewelry, which was once considered shocking or titillating even in casual circles, and is now hardly noteworthy in semi-formal situations. Amelia Bloomer introduced trousers of a sort for women as a casual alternative to formal hoops and skirts. The trend toward female exposure in the 20th century tended to push the necklines of formal ball gowns lower and the skirts of cocktail dresses higher. For men, the exposure of shoulders, thighs, and backs is still limited to casual wear. Gallery Woman cycling while wearing sweater and miniskirt in Canada. A U.S. artist wearing a casual minidress during a public interaction. Woman in crop top and denim shorts A model in T-shirt and cargo shorts. Model in jeans and a military-style shirt. See also Western dress codes Formal wear Semi-formal wear Informal attire Casual wear Smart casual Business casual Workwear Combat uniform Sportswear (fashion) Sportswear (activewear)

With this file you will be able to print Modern Nefertiti, sitting full body with your 3D printer. Click on the button and save the file on your computer to work, edit or customize your design. You can also find more 3D designs for printers on Modern Nefertiti, sitting full body.